Trong loạt bài giới thiệu về Việt Nam đăng trong số tháng 4/2008 của tạp chí The Economist, bài viết dưới đây có thể được đánh giá là một cái nhìn khái quát, súc tích và thú vị về Việt Nam. Bằng những đúc kết từ kinh nghiệm thực tế đã và đang diễn ra ở Việt Nam, thông qua những ẩn dụ và so sánh đơn giản nhưng thuyết phục, bài báo thể hiện một cái nhìn tích cực về một Việt Nam đang cố gắng vươn lên mà không hề gây ra cảm giác về một bài báo PR theo đơn đặt hàng, và lại càng khác so với thể loại báo chí cổ động, tuyên truyền thường thấy. Có lẽ thú vị nhất là sự liên tưởng của tác giả giữa Đạo Cao Đài ở miền Nam Việt Nam với chính sách đối ngoại của Việt Nam, cũng như các lập luận mà tác giả sử dụng để phân biệt Việt Nam với Trung Quốc.

.

***

Dưới đây là bản dịch sang tiếng Việt của Thông tấn xã Việt Nam. Bản dịch này khá sát với bản gốc, tuy cần cải thiện thêm một vài chi tiết nhỏ. Ví dụ, một câu rất đắt trong bài là "Cao Dai's sunny, ecumenical message chimes well with Vietnam's foreign policy of seeking “friends everywhere”" đã được dịch hết sức đại khái và mờ nhạt. Nó nên được dịch là thông điệp lạc quan, mang tính đoàn kết giữa các tôn giáo và tín ngưỡng của Cao Đài rất phù hợp với chính sách đối ngoại "làm bạn với tất cả" của Việt Nam. Hay như, "emulate Deng Xiaoping's market socialism" phải hiểu là "bắt chước", "học tập", hoặc "sao chép"... chứ không phải là ganh đua. Hoặc người dịch lược cụm từ "pursued half-heartedly" trong câu "Vietnam had a two-child policy, pursued half-heartedly", khiến cho câu tiếng Việt trở nên không còn ấn tượng. Nên giữ nguyên gốc và dịch là Việt Nam có chính sách mỗi gia đình có hai con, nhưng chỉ áp dụng nửa vời/ không toàn tâm toàn ý. Hoặc cụm từ "the Great Firewall of China" là cách chơi chữ của tác giả, nói đến tường lửa ở Trung Quốc, nhưng dùng hình ảnh liên tưởng tới một Vạn lý Trường thành trong internet...

.

Việt Nam tìm kiếm mô hình quốc tế điển hình

.

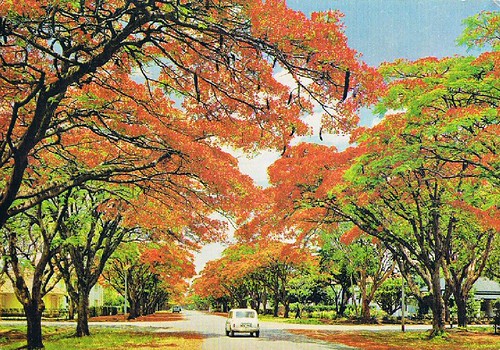

Tiếng chuông ngân lên vào giữa trưa trong một điện thờ sơn phủ sặc sỡ của giáo phái Cao Đài cách Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh 100 km, nơi hàng trăm tín đồ trong trang phục áo choàng sặc sỡ và khăn xếp lòe loẹt đang xếp hàng tiến vào. Họ ngồi xếp bằng giữa những hàng cột sơn màu hồng đắp nổi những con rồng hai mầu xanh và trắng chạm khắc tinh xảo. Khắp xung quanh họ là những biểu tượng của giáo phái này - con mắt thánh: Quang cảnh trông tựa như sự pha trộn giữa một ngôi chùa ở Trung Quốc, một thánh đường Hồi giáo và một nhà thờ Thiên chúa giáo với một chút giống như Thành phố Ngọc Lục Bảo trong câu chuyện huyền bí Wizard of Oz.

Cao Đài, một tôn giáo trong nước mang tính hòa hợp của Việt Nam, pha trộn giữa đạo Phật, đạo Lão, đạo Cơ đốc, đạo Hồi và những tôn giáo khác, giáo huấn rằng tất cả những niềm tin là sự biểu thị của "cùng một chân lý". Giáo phái này được sáng lập vào năm 1926 bởi Ngô Văn Chiêu, một công chức nhà nước. Đến những năm 40, Cao Đài đã phát triển thành một lực lượng mạnh có quân đội riêng. Giáo phái này từng ủng hộ sự chiếm đóng của Nhật Bản và đôi khi cả với chế độ thân Mỹ ở miền Nam Việt Nam, vì thế sau năm 1975 Cao Đài bị những người cộng sản kiềm chế. Đến nay, khi chính phủ xóa bỏ những hạn chế tôn giáo, Cao Đài đã quay được sự ưa chuộng trở lại mặc dù vẫn phải chịu sự kiểm soát chặt chẽ. Tháng 2/2008, các thành viên của Ủy ban Tôn giáo Chính phủ đã tham dự một buổi hành lễ cùng 200.000 tín đồ Cao Đài tại một điện thờ lớn.

Sự phát triển trở lại của đạo Cao Đài đi kèm với chính sách đối ngoại của Việt Nam mong muốn "làm bạn với tất cả các nước". Nói một cách rộng hơn, niềm tin tôn giáo phản ánh đặc điểm tinh hoa của dân tộc Việt Nam, đó là tìm kiếm những khuôn mẫu tiêu biểu, sau đó tìm cách đưa những nét nổi bật của mình vào trong những khuôn mẫu đó theo cách thức phù hợp của Việt Nam. Đặc điểm này đã xuất hiện một cách tự nhiên ở một đất nước từng bị xâm chiếm và đô hộ bởi quá nhiều thế lực ngoại bang. Hệ thống luật pháp của Việt Nam hiện nay chủ yếu dựa trên những nguyên tắc pháp lý thuộc Pháp, nhưng lại có những thay đổi để phù hợp với các mô hình của Trung Quốc và Liên Xô cũ. Khi Việt Nam còn nằm dưới sự che chở của Liên Xô trong suốt thời kỳ Chiến tranh Lạnh, họ đã bắt chước mô hình kinh tế chủ nghĩa tập thể của nước này và để lại những hậu quả thảm khốc. Tiếp theo đó, Việt Nam lại ganh đua với mô hình chủ nghĩa xã hội thị trường của Đặng Tiểu Bình. Gần đây, họ lại được thuyết phục bởi các đặc điểm trong mô hình tăng trưởng xóa đói giảm nghèo của các cơ quan Liên Hợp Quốc và Ngân hàng Thế giới cũng như các lý thuyết nền tăng của hệ thống phúc lợi xã hội ở các nước châu Âu.

Dấu ấn Trung Quốc

Những phát triển gần đây cho thấy Việt Nam đáng được xem là một Trung Quốc thu nhỏ khi mà cả hai nước đều được lãnh đạo bởi những người cộng sản tiểu tư bản hăng hái, nhưng giữa họ có sự khác biệt. Một nhà ngoại giao ở Hà Nội từng làm việc ở Bắc Kinh cho rằng "mọi thứ ở đây (Việt Nam) đều có chừng mực hơn ở Trung Quốc". Việt Nam ít thô bạo hơn đối với những người bất đồng chính kiến so với Trung Quốc và "răng nanh và móng vuốt" của chủ nghĩa tư bản ở đây cũng ít bị nhuộm đỏ hơn. Dịch vụ y tế và giáo dục đã thay đổi để thành công hơn khi chuyển đối sang kinh tế thị trường. Sự kiểm soát của Việt Nam, giống như ở Trung Quốc, chính là những hạn chế nghiêm ngặt, tuy nhiên, số lượng người sử dụng Intemet có thể truy cập vào các trang web ở nước ngoài ngày càng nhiều hơn: người sử dụng Internet Việt Nam không bị chặn bởi bức "Tường lửa khổng lồ" như ở Trung Quốc.

Trong khi Trung Quốc nằm dưới sự lãnh đạo xuyên suốt và rõ ràng của một nhà lãnh đạo tối cao - Hồ Cẩm Đào, người nắm giữ hai chức vụ Tổng Bí thư Đảng Cộng sản và Chủ tịch nước - thì Việt Nam có sự lãnh đạo tập thể. Ba trụ cột gồm Chủ tịch nước, Tổng bí thư Đảng và Thủ tướng phải đạt được sự đồng thuận cùng với vai trò ngày càng gia tăng của Quốc hội độc lập và các lực lượng quần chúng khác, đồng thời tránh làm xáo trộn nhóm anh hùng cựu chiến binh trong các cuộc chiến tranh giành độc lập của Việt Nam vẫn đang còn sống. Lãnh đạo Trung Quốc có thể ra lệnh phá hủy các dự án công trình công cộng bất chấp những hậu quả. Ngược lại, quá trình ra quyết định ở Việt Nam có vẻ như "hợp tình hợp lý hơn".

Trung Quốc áp dụng nghiêm ngặt "chính sách một con"; Việt Nam có "chính sách hai con". Trong khi dân số Trung Quốc đang già đi thì thế hệ trẻ em sinh sau chiến tranh ở Việt Nam đang bước vào độ tuổi sung sức nhất, tăng trưởng kinh tế nhanh cũng đã tạo thêm nhiều công ăn việc làm cho tất cả mọi người. Giám đốc ngân hàng HSBC tại Việt Nam, Tom Tobin nhận xét rằng trong một hoặc hai thập niên tới, trong khi đa phần dân số của thế giới già đi nhanh chóng, lớp thanh niên Việt Nam vẫn sẽ ở giai đoạn sung sức nhất trong sự nghiệp của họ.

Trung Quốc vẫn là một mô hình tiêu biểu kết hợp giữa các cải cách thị trường với tư tưởng cộng sản chủ nghĩa, cho dù đa số người Việt Nam phải miễn cưỡng thừa nhận rằng họ đang bắt chước kẻ thù ngàn năm của họ. Tuy nhiên, đảng cầm quyền Việt Nam cũng hướng tới sự giàu có của Singapore - tuy danh nghĩa là một nền dân chủ thị trường tự do nhưng thực tế là một quốc gia một đảng, nơi chính quyền vẫn kiểm soát những cấp độ chủ đạo của nền kinh tế. Ví dụ, Việt Nam đã xây dựng mô hình giống như tập đoàn Temasek - Công ty đầu tư Singapore quản lý cổ phần của nhà nước tại các doanh nghiệp bán tư nhân. Rõ ràng là Việt Nam quá lớn và quá phi tập trung hóa để có thể bắt chước mô hình của nước Singapore nhỏ bé, tuy nhiên, Đảng Cộng sản hy vọng rằng họ sẽ đúc kết được những kinh nghiệm của Đảng Hành động Nhân dân Singapore (PAP) thuyết phục cử tri tiếp tục chấp nhận vai trò lãnh đạo của họ như cái giá của sự thịnh vượng. Giống như PAP, Đảng Cộng sản Việt Nam tìm kiếm cơ hội thu hút những nhân tài và đầu tư cho các nhân sự nội bộ trong giai đoạn đầu này.

Nhận thức được giáo dục cao và cải tiến khoa học đã là những nhân tố then chốt làm nên sự giàu có của Nhật Bản, Hàn Quốc và Đài Loan, Việt Nam đang khuyến khích các tập đoàn công nghệ cao nước ngoài và mời gọi những nước giàu xây dựng các trường đại học, các cơ sở đào tạo trên đất nước họ. Một trường đại học Australia, Đại học Công nghệ Hoàng gia Melbourne (RMIT) đã mở các cơ sở đào tạo ở Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh và Hà Nội. Một trường đại học của Đức và một số trường cao đẳng công nghệ khác của Hàn Quốc cũng đang có kế hoạch thành lập. Trong khi đó, các gia đình Việt Nam, từ Thủ tướng, đang gửi con em đi học nước ngoài.

Vậy thì, nền kinh tế dung hợp của Việt Nam sẽ theo đuổi mô hình nào? Bởi vì Việt Nam đang tìm kiếm cơ hội xây dựng các tập đoàn kinh tế quốc gia mạnh, họ chưa biết chắc nên theo đuổi mô hình "keiretsu" của Nhật Bản, "chaebol' của Hàn Quốc hay mô hình các tập đoàn chuyên sâu trong một lĩnh vực kinh doanh chủ chốt kiểu Anh. Có lẽ họ sẽ cóp nhặt những gì tinh túy nhất từ những mô hình này. Nhưng, Tony Salzman, một doanh nhân người Mỹ ở Việt Nam lại lo ngại về mối đe dọa khi "râu ông nọ cắm cằm bà kia!"

***

Dưới đây là bản dịch sang tiếng Pháp của TMH. Bản dịch này lược bỏ đoạn văn đầu vì không có nội dung phân tích:

La quête des modèles au Vietnam

Le Caodaïsme (Cao-Dai en vietnamien signifie « être suprême »), religion syncrétiste qui n’existe qu’au Vietnam, mélange le Confucianisme, le Bouddhisme, le Taoïsme, le Christianisme, l’Islam et d’autres religions en enseignant que toutes les fois représentent des manifestations d’une « même vérité ». Cette religion a été établie en 1926 par un fonctionnaire vietnamien. Dans les années 1940 il était devenu une force puissante possédant sa propre armée privée. Il a appuyé l’occupation japonaise et parfois le régime proaméricain du Vietnam du Sud. Il a été, donc, réprimé par les communistes après 1975. Aujourd’hui, comme le gouvernement est moins sévère envers des religions, le caodaïsme a repris la faveur, quoiqu’il soit strictement contrôlé. En février, des responsables du comité des affaires religieuses du gouvernement ont rejoint 200 mille caodaïstes dans un rituel effectué au grande temple caodaïste, à environ 100 km de Saigon.

Le message œcuménique du caodaïsme s’accorde bien avec la politique extérieure de « chercher des amis partout » du Vietnam. Plus globalement, la foi reflète un trait fondamentalement vietnamien : chercher des modèles et puis mêler les meilleurs aspects d’un certain nombre d’entre eux dans quelque chose d’uniquement commode pour le pays.

Cela peut arriver à un pays qui a été occupé et influencé par tant de puissances étrangères. Le système juridique vietnamien se base essentiellement sur les principes napoléoniens mais avec de petits morceaux adaptés des modèles chinois et soviétiques. Lorsque le Vietnam était sous l’aile de l’Union soviétique pendant la guerre froide, il a calqué son économie sur le modèle collectiviste, ce qui a entraîné des conséquences désastreuses. Ensuite, il a émulé le socialisme de marché de Deng Xiaoping. Plus récemment, il a greffé des éléments des modèles de la croissance anti-pauvreté initiés par la Banque Mondiale et par des agences onusiennes. Le pays a également copié les rudiments d’un état de bien-être pratiqué en Europe.

Il est tentant de voir le Vietnam comme étant une mini Chine car tous les deux pays sont dirigés par des communistes ardemment capitalistes, mais il y a des différences. Un diplomate étranger qui servait à Pékin dit que « tout est plus modéré ici qu’en Chine ». Le Vietnam est un peu moins sévère envers des dissidents que la Chine et son capitalisme est moins sauvage. Ses services de la santé et de l’éducation se sont adaptés avec plus de succès à la transition à une économie de marché. Bien que la presse au Vietnam, comme en Chine, soit strictement contrôlée, les nombres croissants d’internautes au Vietnam ont l’accès à la plupart des sites web étrangers. Il n’y a pas un équivalent vietnamien pour le Grand Pare-feu de Chine.

La Chine est dirigée de haut en bas et un homme est clairement le leader suprême- Hu Jintao, qui est à la fois chef du parti communiste et président de l’Etat, tandis que le Vietnam maintient un leadership consensuel. Son triumvirat comprenant le président, le chef du parti et le premier ministre doit aboutir aux accommodations avec une assemblée nationale qui est de plus en plus indépendante et avec une foule d’autres forces, ainsi qu’éviter de fâcher de nombreux héros survivants des guerres d’indépendance du pays. Le leadership de Chine peut s’ingérer dans des projets des travaux publics quelles que soient les conséquences. Par contraste, le processus décisionnel au Vietnam peut sembler terriblement lent mais aussi plus équitable.

La Chine a strictement appliqué la politique de l’enfant unique ; le Vietnam a eu la politique de deux enfants qui a été suivie sans conviction. La population de Chine a déjà vieilli alors que les personnes du baby-boom post-guerre au Vietnam sont en train d’entrer dans leur apogée et que la croissance économique rapide a donné des emplois à eux tous. Tom Tobin, chef de HSBC au Vietnam note que dans une ou deux décennies, le moment où la plupart du reste du monde vieillira rapidement, les personnes du baby-boom au Vietnam seront dans la phase la plus productive de leurs carrières.

La Chine demeure le modèle le plus évident pour la combinaison entre des réformes de marché et l’idéologie communiste, bien que la majorité des Vietnamiens préféreraient ne pas admettre qu’ils ont calqué leur système sur le modèle de leur ancien ennemi. Certes, le parti dirigeant du Vietnam compte également sur Singapour, un pays riche qui est nominalement une démocratie de marché libéral mais, dans la pratique, un état à parti unique dont le gouvernement contrôle les secteurs pivots de l’économie. Par exemple, le Vietnam a créé une copie carbone de Temasek, une agence d’investissement singapourienne, pour garder ses participations dans les sociétés qui sont en partie privatisées .

Evidemment, le Vietnam est trop gros et trop décentralisé pour pouvoir se calquer sur le petit Singapour. Cependant le parti communiste du Vietnam espère jouer le même tour que celui du Parti d’Action du Peuple (PAP) de Singapour en convainquant les électeurs d’accepter sa direction continue comme le prix pour la prospérité. Comme le PAP, les communistes vietnamiens cherchent à recruter des ambitieux universitaires ainsi que des penseurs naissants dans leur petit groupe à un stade précoce.

Notant que l’enseignement supérieur et l’innovation scientifique sont clés à la richesse pour le Japon, la Corée du Sud et Taiwan, le Vietnam courtise des sociétés de haute technologie étrangères et invite des pays riches à ouvrir des universités et des installations de formation sur son territoire. L’Institut Royal de la Technologie de Melbourne a déjà ouvert ses campus ultramodernes à Ho Chi Minh ville et à Hanoi. Une université allemande et plusieurs collèges coréens ont déjà été planifiés. Entre temps, des familles vietnamiennes, de celle du premier ministre vers le bas, envoient actuellement leurs enfants à l’étranger pour faire leurs études.

Alors, quelle forme l’économie syncrétiste du Vietnam va-t-elle prendre ? Comme le pays cherche à construire des sociétés nationales fortes, il n’est pas encore sûr s’il va se modeler sur le keiretsu japonais, le chaebol coréen ou les compagnies anglo-saxonnes qui se concentrent sur leurs affaires centrales. Peut-être se débrouille-t-il pour prendre les meilleurs morceaux de chaque modèle. Toutefois, Tonly Salzman, homme d’affaires américain au Vietnam, s’inquiète du danger du « col qui ne va pas avec les manchettes ».

***

Bản gốc tiếng Anh :

VIETNAM

A bit of everything

Apr 24th 2008

From The Economist print edition

Vietnam's quest for role models

A BELL chimes at noon in the pastel-coloured Cao Dai Grand Temple, about 100km (63 miles) from Ho Chi Minh City, and hundreds of worshippers in coloured robes and a variety of headgear file in. They sit cross-legged among pink columns with carvings of gaudy green-and-white dragons. All around them is their religion's symbol, the all-seeing eye. The place looks like a cross between a Chinese temple, a mosque and a Catholic church, with a touch of the Wizard of Oz's Emerald City.

Cao Dai, Vietnam's syncretistic home-grown religion, mixes Buddhism, Taoism, Christianity, Islam and other religions, teaching that all faiths are manifestations of “one same truth”. The religion was founded in 1926 by Ngo Van Chieu, a government official. By the 1940s it had become a powerful force, maintaining its own private army. It supported the Japanese occupation and at times the pro-American South Vietnamese regime, so after 1975 it was repressed by the Communists. Now, as the government eases up on religion, Cao Dai is back in favour, albeit strictly controlled. In February members of the government committee for religious affairs joined 200,000 Caodaists for a grand ritual at the temple.

Cao Dai's sunny, ecumenical message chimes well with Vietnam's foreign policy of seeking “friends everywhere”. More broadly, the faith reflects a quintessentially Vietnamese trait: casting around for role models, then trying to meld the best aspects of several of them into something uniquely suited to Vietnam.

That may come naturally to a country that has been occupied and influenced by so many foreign powers. The Vietnamese legal system is based mainly on Napoleonic principles but with bits adapted from the Chinese and Soviet models. When Vietnam was under the Soviet Union's wing during the cold war, it copied its collectivist economic model, with disastrous results. Next, it emulated Deng Xiaoping's market socialism. More recently it has grafted on elements of the World Bank's and UN agencies' anti-poverty growth models and, increasingly, the rudiments of a welfare state along European lines.

China lite

It is tempting to view Vietnam as a mini-China, since both countries are run by ardently capitalist communists, but there are differences. A foreign diplomat in Hanoi who used to serve in Beijing says that “everything here is more moderate than in China.” Vietnam is a bit less harsh with dissidents than China, and its capitalism too is less red in tooth and claw. Its health and education services have adapted more successfully to the transition to a market economy. Its press is strictly controlled, as in China, but the growing numbers of internet surfers have free access to most foreign news websites: there is no Vietnamese equivalent of the Great Firewall of China.

Whereas China is led from the top down and one man is clearly the paramount leader—Hu Jintao, who is both the head of the Communist Party and the state president—Vietnam has a consensual leadership. Its triumvirate of president, party boss and prime minister must reach accommodations with an increasingly independent national assembly and a host of other forces, and avoid upsetting the many surviving heroes of Vietnam's independence wars. China's leadership can ram through public-works projects regardless of the consequences. In contrast, the decision-making process in Vietnam can seem painfully slow—but also more equitable.

China enforced a one-child policy harshly; Vietnam had a two-child policy, pursued half-heartedly. Whereas China is already greying, Vietnam's post-war baby-boomers are now coming into their prime, and rapid economic growth has been providing jobs for them all. HSBC's chief in Vietnam, Tom Tobin, notes that in a decade or two, when much of the rest of the world will be ageing rapidly, Vietnam's boomers will still be at the most productive phase of their careers.

China remains the most obvious role model for combining market reforms with communist ideology, though most Vietnamese would be loth to admit to copying their ancient foe. But Vietnam's ruling party also looks to rich Singapore, nominally a free-market democracy but in practice a one-party state whose government still controls the commanding heights of the economy. For example, Vietnam has created a carbon copy of Temasek, a Singaporean investment agency, to retain its stakes in part-privatised firms.

Clearly Vietnam is too big and too decentralised to be able to copy tiny Singapore, but its Communist Party hopes to pull off the same trick as Singapore's People's Action Party (PAP), persuading the voters to accept its continued rule as the price of prosperity. Like the PAP, the Vietnamese Communists seek to recruit academic high-flyers and budding thinkers to their inner circle at an early stage.

Noting that higher education and scientific innovation were the keys to riches for Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, Vietnam is wooing foreign high-tech firms and inviting rich countries to set up universities and training facilities on its soil. An Australian university, the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, has already opened state-of-the-art campuses in Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi. A German university and several South Korean technical colleges are planned. Meanwhile families from the prime minister's downwards are sending their youngsters to study abroad.

So what shape will Vietnam's syncretistic economy take? As the country seeks to build strong national companies, it is as yet unsure whether to model them on Japanese keiretsu, Korean chaebol or Anglo-Saxon companies that focus on their core business. Maybe it will manage to take the best bits of each model. But Tony Salzman, an American businessman in Vietnam, worries about the danger of “the collars not matching the cuffs”.