| Xung quanh những phát biểu của Hạ nghị sỹ Mỹ Loretta Sanchez với báo chí tại Hà Nội (6/4/2007), bà Tôn Nữ Thị Ninh, Phó Chủ nhiệm Ủy ban Đối ngoại của Quốc hội Việt Nam đã trả lời phỏng vấn TTXVN:

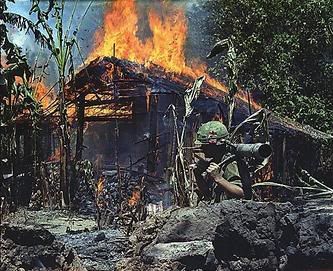

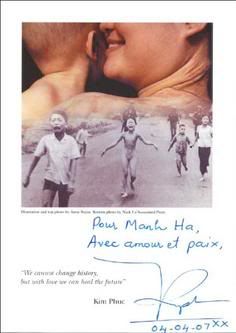

Bà có nhận xét gì đối với những lời chỉ trích gay gắt của Hạ nghị sỹ Loretta Sanchez về dân chủ và nhân quyền tại Việt Nam? Trước hết, bà Loretta Sanchez chưa bao giờ đến Việt Nam với một thái độ cởi mở, khách quan, thực sự nhìn nhận toàn cảnh tình hình Việt Nam. Bà đến Việt Nam không phải để tìm hiểu và trao đổi mà để thực hiện một chương trình “can dự” riêng theo sự xúi giục của một nhóm cử tri cực đoan tại California vẫn đang chìm đắm trong quá khứ. Tiếc rằng thay vì quan tâm đến đa số cử tri là những người hướng tới tương lai nhưng lại không lớn tiếng, bà lại để bản thân trở thành con tin của nhóm cử tri lỗi thời. Do đó, chúng tôi không hề ngạc nhiên trước những bình luận đen tối, kích động về tình hình Việt Nam của bà Sanchez. Mặt khác, Hạ nghị sỹ Loretta Sanchez lại phớt lờ những mối quan tâm của chính Việt Nam về nhân quyền. Bà từ chối, hoặc làm ngơ những đề nghị tiếp xúc của Hội Cựu Chiến binh Việt Nam và Hội nạn nhân chất độc da cam/dioxin yêu cầu trao đổi về vấn đề chất độc da cam hay từ chối đến thăm Làng Hữu nghị nơi chăm sóc những nạn nhân chất độc da cam/điôxin. Hơn nữa, trong thời gian ở thăm Việt Nam, những hành vi không phù hợp của bà là sự can thiệp trắng trợn vào công việc nội bộ của Việt Nam dưới chiêu bài “đem dân chủ” từ bên ngoài đến Việt Nam. Những hành động này của bà không có lợi cho sự phát triển của quan hệ Hoa Kỳ-Việt Nam. Chúng tôi chỉ tin tưởng vào một nền dân chủ do chính mình tạo dựng, và đã qua lâu rồi thời kỳ những nước đang phát triển cần các nước phát triển đến khai sáng và cứu rỗi. Chúng tôi thấy khó hiểu những đại biểu dân cử như bà Loretta Sanchez lại quan tâm quá mức và tốn nhiều sức lực cho vấn đề nhân quyền ở nước ngoài, như Việt Nam. Có lẽ những nỗ lực và sự quan tâm đó sẽ mang tính xây dựng và phù hợp hơn nếu được dành cho những vấn đề “gần nhà hơn” ví dụ như vấn đề Guantanamo. Như vậy, có phải là chuyến thăm Việt Nam của đoàn Nghị sỹ Hoa Kỳ không có hiệu quả? - Tôi không nghĩ vậy. Đoàn có 3 Hạ nghị sỹ khác của Uỷ ban Quân lực Hoa Kỳ, và trong số đó có 2 Hạ nghị sỹ thuộc Nhóm các Hạ Nghị sỹ Hoa Kỳ quan hệ với Việt Nam. Chúng tôi đã có những cuộc trao đổi với tinh thần xây dựng trên nhiều vấn đề trong tổng thể quan hệ song phương như hợp tác MIA và an ninh, cũng như quan hệ kinh tế thương mại. Chúng tôi hoan nghênh đoàn nghị sỹ đầu tiên của Quốc hội mới, đặc biệt vì đây là đoàn đại biểu đầu tiên của Uỷ ban Quân lực Hạ viện, coi đây là một bước tiến thiết thực triển khai thoả thuận chung đã được Chủ tịch Quốc hội hai bên thống nhất một năm trước để tăng cường giao lưu và tiếp xúc giữa các nghị sỹ Hoa Kỳ và Việt Nam, nhằm không ngừng đưa quan hệ Việt Nam-Hoa Kỳ phát triển theo chiều rộng và chiều sâu. (TTXVN) Một số bình luận của độc giả BBC Đức, Hà Nội

Nên thông cảm, chính trị phải như thế. Việc làm của bà Loretta Sanchez trong chuyến thăm Việt Nam có thể không giống như bà này nghĩ về Việt Nam. Tuy nhiên, làm chính trị chuyên nghiệp kiểu như dân biểu Mỹ, bà phải như con tắc kè hoa thì mới thọ được. Âu cũng là cái nghiệp của nhà chính trị. Về Mỹ, có khi bà này chẳng nhớ mình đã nói gì ở Việt Nam đâu. Thêm nữa, bà này đâu rành tiếng Việt. Nắm bắt thông tin về Việt Nam mà phải qua phiên dịch thì thông tin cũng đã bị tam sao thất bản đôi phần, nên thông cảm cho bà ấy. Ở Mỹ, có những học giả người Mỹ nghiên cứu về Việt Nam hàng vài chục năm, sang Việt Nam nhiều lần, nói tiếng Việt rành rẽ, vậy mà họ đâu có nói Việt nam tệ đến thế. Còn quan điểm về nhân quyền, nó cũng giống như qua! n niệm về hạnh phúc vậy, mỗi người mỗi vẻ chẳng ai giống ai. Với nhiều người Việt Nam bây giờ, rất thiết thực, cứ làm việc có tiền xây nhà sắm xe, đi du lịch... thế là đủ nhân quyền. Nguyen Dan, SJ, US

Dan Nguyen, San Jose, CA (USA) Chỉ vì một vài người bất đồng ý kiến mà bà Sanchez kêu gọi Mỹ trừng phạt chống đối lại Việt Nam, một đất nước đang có hơn 85 triệu dân đang được sống một cuộc sống thanh bình và hạnh phúc. Đây là nhân quyền mà bà ta muốn đem đến cho nhân dân Việt Nam đó ư??? Theo tôi, đó cũng vì hận trong lòng của bà chất chứa từ bấy lâu nay mà thôi. Phải chăng vì Việt Nam đã nhiều lần khước từ không chịu cấp Visa cho bà nhập cảnh Việt Nam là chuyện mất mặt nhất trong đời của bà? Đây là "mối hận thù ngàn thu", cho nên khi được dịp là bà Sanchez trút hết mối hận này ra đó mà. Chẳng lạ lùng gì đối với bà. Huỳnh Văn Hậu, USA

Thưa quý vị Việt kiều, nếu không có CSVN liệu khi quý vị vượt biên, vượt biển có được các nước khác chấp nhận cho cư trú hay không? Nếu quý vị là sĩ quan viên chức chế độ cũ có được CSVN cho ra đi có trật tự theo diện HO, diện đoàn tụ hay không? Mà bây giờ quý vị hùa theo Mỹ, yêu cầu Mỹ lên án nhân quyền của CSVN? Dân trong nước đang được sống yên ổn, không muốn suy nghĩ xa vời, xin quý vị đừng làm khổ họ với phân tách nhân quyền phải thế này, dân chủ phải thế kia. Tôi hiện nay đang sống ở Mỹ, nên hỏi những điều trên có thể khiến nhiều người đa nghi cho tôi thuộc thành phần CS nằm vùng, thuộc thành phần hoạt động theo nghị quyết 36 của đảng nhắm vào người Việt hải ngoại, tạo hỏa mù dư luận bên ngoài tuyên truyền cho người trong nước là VN không thua kém các nước khác, nhưng vì sự thật tôi không thể im lặng. Hoan Lạc

Tôi rất hoan nghênh việc làm của bà Sanchez. Nếu không có người như bà thì chính phủ CS Việt Nam sẽ đàn áp và khủng bố nhân dân VN mà vẫn che mặt được thế giới. Tôi rất mong bà dùng ảnh hưởng của mình để buộc chính quyền VN phải tôn trọng nhân quyền và tự do tôn giáo. Nam Trần, Úc

Nhân quyền ... vô cùng nhạy cảm đối với nhà cầm quyền Hà Nội. Chính quyền cứ ra rả về thành tích nhân quyền của họ, nhưng lại dễ ...tổn thương với những tác động của lĩnh vực này. Nếu chính phủ các ông có thành tích nhân quyền tốt thì chỉ phản ứng của một dân biểu nước ngoài thì xá gì mà các ông quá căng thẳng như vậy? Hành động côn đồ với dân tộc mình là chuyện cơm bữa của các ông. Ngay cả nơi chốn pháp đình trang nghiêm mà người dân còn bị các ông bịt mồm , bẻ tay thì việc các ông có ...xô đẩy và hành hung vài chị phụ nữ trước mặt ông đại sứ và bà dân biểu ngoại quốc cũng là ...bình thường thôi mà. Các ông cứ an tâm tự tại mà chờ ngày 80 triệu dân này đứng lên đòi quyền tự do nhé! Ngô Quốc Khôi, Korea

Việt Nam luôn muốn được có cuộc sống hòa bình, luôn hướng đến một tương lai tốt đẹp. Hiện nay, có những thế lực trong và ngoài nước đang gây sức ép lớn đến nền kinh tế và chính trị ở Việt Nam. Tại sao họ lại phải làm như vậy trong khi chính họ là những người con đất Việt. Không lẽ họ cứ muốn gây chết chóc và đau thương cho nhân loại hay sao. Tôi mong trước hết dù bất cứ ở đâu là những người Việt hãy xóa bỏ hận thù cùng nhau chung sức xây dựng hoàn thiện đất nước trở thành con rồng của Châu Á. Bon Bon, Paris

Trước tiên, phải công nhận rằng BBC là một diễn đàn "tương đối" tự do để mọi người bày tỏ quan điểm. Tuy nhiên, đừng nghĩ rằng bạn viết gì cũng được post vì tôi và bạn tôi có một số lần bày tỏ quan điểm của mình trên diễn đàn nhưng không được post. Thứ hai: Rất tiếc truyền hình VN không "truyền hình trực tiếp" phiên xử Cha Lý. Đúng là trên báo chí có đăng hình ảnh 1 người "có vẻ" bịt miệng cha Lý, nhưng theo tôi các bạn hãy đợi hình ảnh Video vì nhìn ảnh thì rất khó, có thể cha Lý mệt quá bị ngã, nếu không đỡ đầu cha Lý, nhỡ miệng cha Lý va vào vành móng ngựa gãy hết răng thì sao? Còn ai để các "bạn Mỹ" nhờ nữa. (Cũng giống như hình ảnh báo chí VN đăng tin CA giúi đầu nhà báo trong vụ PMU 18, sau mới biết anh CA đỡ cánh cửa cuốn đấy thôi). Thứ ba: Mọi người cũng phải thông cảm cho bà Sanchez, bà ta đại diện cho cử tri bên Mỹ thì bà ta phải làm những gì dân yêu cầu. Điều này VN quả còn phải học nhiều. Nói đi cũng phải nói lại, ông cha ta có câu: mỗi cây mỗi hoa, mỗi nhà mỗi cảnh. Ở thành thị thì đa số mọi người hiểu biết, ở nông thôn đời sống khó khăn, ít người quan tâm đến chính trị, do vậy Đại biểu quốc hội có về tiếp xúc cử tri thì cũng thế thôi. Họ còn bận đi làm cở lúa, đi chăn bò, đi làm rừng ... Chắc là phải đợi đến khi mỗi nhà có 1 cái ôto Loncin, Lifan nhé. Thứ tư: Tôi khẳng định có rất nhiều người Việt ở Mỹ có thiện chí với quê hương, nhưng phải nói có nhiều người còn rất cay cú. Các bạn cứ xoáy vào việc "an ninh" VN ngăn cản bà này, bà kia. Tôi được biết khi một số lãnh đạo VN thăm Mỹ cũng bị một số người ném cái này cái nọ, la ó. Cuối cùng tôi xin khẳng định tôi là 1 người dân bình thường, không phải là CA cài vào để viết bài. Tôi không biết bài có được Post không?! Phan Nguyễn, TP HCM

Tôi không hiểu bà Loretta Sanchez và mấy vị "dân bểu" Mỹ khác đến Việt Nam để "xem xét vấn đề nhân quyền" với tư cách gì? Dân biểu ư? Vậy thì mời bà về Mỹ, ở đây bà không đại diện cho ai cả, những kẻ bỏ phiếu cho bà đang ở bên kia bờ đại dương, họ mang quốc tịch Mỹ, sống theo lối sống Mỹ, nếu cần xem xét về dân chủ thì bà nên xem lại ở chính quốc gia của mình xem dân chủ kiểu, nhân quyền đã tốt chưa. Tôi đề nghị Chính phủ Việt Nam trục xuất ngay mụ này ra khỏi lãnh thổ Việt Nam trong 24 giờ, chắc chắn rất nhiều người Việt Nam chân chính, có tinh thần dân tộc và biết tự trọng về nguồn gốc của mình sẽ đồng tình với quyết định này. Trần Toàn, Slovakia

Vị dân biểu này thật đáng thương, may mà bà ta sang VN chứ bà ta mà ở một đất nước khác có nền dân chủ kiểu Mỹ thì chắc chắn phải đội ô để tránh chứng thối rồi. Việc làm của bà ta làm tôi liên tưởng đến một con rối. Ẩn danh

Các ông nghị VIệt Nam mà được 1/10 sự hăng hái làm việc cho cử tri như bà Sanchez thì may mắn cho dân nghèo biết mấy. Bà Sanchez chẳng qua là đại diện cho ý muốn của những người mà chính phủ Việt Nam cho là lạc tông, lạc điệu, trong bài ca xây dựng đất nước. Lạc điệu hay không, họ vẫn đang đóng góp ít nhất 20% tổng sản lượng quốc gia Việt Nam bằng ngoại tệ mạnh. Nếu thay thế 3 triệu đảng viên bằng 3 triệu kiều bào, chắc chắc nước Việt Nam sẽ khá hơn bây giờ rất nhiều. Vo Van

Ai nói là chất độc da cam, thăm làng Hữu Nghị... là việc làm từ thiện???, nếu là một đại sứ nước khác thì có thể nói như thế, chất độc da cam là do Mỹ gây ra, Mỹ phải có trách nhiệm trong việc cùng VN khắc phục hậu quả của chất da cam chứ không phải là làm từ thiện. Phi Hung, Tp HCM

Tôi thì lại băn khoăn là tại sao không trục xuất bà Sanchez này ra khỏi Việt Nam nhỉ? Tôi thấy phản ứng và phát biểu của Bà Tôn Nữ Thị Ninh là sâu sắc, thâm thúy và đầy đủ. Bà Sanchez có lẽ chưa đủ uyên thâm để hiểu hết ý nghĩa các phát ngôn của bà Ninh nên vẫn cứ loăng quăng ở Việt Nam. Còn ông Đại Sứ Hoa Kỳ ở Việt Nam? chẳng lẽ ông ta chưa bao giờ ra đường để mà quan sát tình hình và cuộc sống của người dân thế nào hay sao mà để cái bà này phát biểu linh tinh? Bao nhiêu Việt Kiều về nước làm ăn giàu lên thấy rõ, chỉ có những người không có khả năng, thếu vốn liếng thì mới ngồi nhà gặm nhấm nỗi buồn thất nghiệp rồi đâm ra quẫn trí rồi đâm ra hằn học. Nói thật, nếu bạn là một Việt Kiều đang gửi tiền về nuôi thân nhân hoặc đầu tư thì bạn không bao giờ mong muốn đến việc kích động để đưa ra cái chế tài về kiều hối kia đâu đúng không? Chắc có lẽ việc lùm xùm này không phải chỉ do một nhóm cử tri thất sủng kích động mà còn được sự tham gia của nhóm tạm gọi là "ghen ăn tức ở" với các Việt Kiều chân chính" nữa. Bà Sanchez sao không gặp bà Tôn Nữ Thị Ninh để đàm đạo nhỉ? Tôi nghĩ lý kém thì ắt phải to mồm như bà Sanchez vậy. Nhưng dù sao thì bà ta cũng kiếm được ít phiếu ở Mỹ. Long, Paris

Theo luật quốc tế về Ngoại giao, Việt Nam hoàn toàn có thể tuyên bố Personna Non Grata với Bà Sanchez và tống cổ bà này ra khỏi lãnh thổ Việt Nam vô điều kiện! Long, TP HCM

Bà Sanchez đơn giản chỉ biết người Viet ở California thôi. Bà làm gì có sự hiểu biết người Viêt tại Vietnam. Bà này cũng chỉ là nhóm "bốc đồng" nghĩ về chuyện xưa mà bình chuyện nay. Cuộc sống thay đổi nhiều rồi, người dân Vietnam ngày nay có khi lại sung sướng, hạnh phúc và nhiều tiền hơn nhóm Viet Kieu gì gì đó ở Mỹ. Tôi từng học ở Mỹ và hiểu rõ người Viet ở Mỹ sống bằng gì, nail, waiter, dish washer, v.v.... và họ chỉ biết nói tiếng Anh lỏm bỏm. Những người thành công ở Mỹ, họ đã hòa nhập cuộc sống ở Mỹ rồi, và có nhiều công việc chứ chẳng có dư thời gian mà "bình thiên hạ". Ngày xưa có máy bay tàu chiến, xe tăng thiết giáp, đánh đấm còn không thắng. Ngày nay thì có mỗi cái lưng quần mà cứ hay gào thét. Quên đi, lo làm ăn đi mấy anh chị, nếu có chút tiền thì về Vietnam mà xem. Còn tính mua nhà mua xe ở Vietnam thì đem về tối thiểu vài triệu USD rồi hãy nói. |