Mr President,

This is what you are quoted by BBC just now as saying yesterday "Just like in Vietnam, if we would leave before the job here [Iraq] is done, these enemies would follow us home" (BBC worldservice 23 Aug.2007).

Don't you think such an analogy is, again, oversimplified ?

And this is what I wrote 3 years ago:

The Gulf is no Vietnam

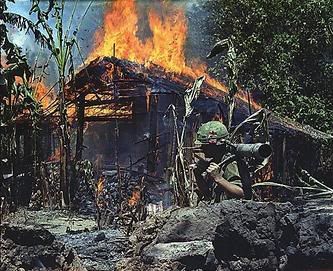

‘No two wars are alike.’[1] The analogy between Vietnam and the Gulf, therefore, was flawed in many particulars. There are a number of important distinctions between the Persian Gulf War of 1991 and the Vietnam War. The most important one is obvious, that the Vietnam War belonged to the Cold War era while the war in the Persian Gulf was ‘the first post- Cold War crisis.’[2] In the post-Cold War era, ‘the argument over ideology had largely disappeared.’[3] There was little concern about the disposition of the Soviets or the Chinese in the Gulf Crisis as there had been in Vietnam. China’s borders, of course, were not threatened by the US action in Kuwait, and the Soviet Union in 1991 was on the verge of economic and political disintegration. Donaldson observed, ‘for the first time since World War II the United States could initiate a major military intervention outside its own hemisphere without having to fear Communists reprisals, and without the fear that the war might escalate into a nuclear war.’[4] And while the United Nations was made paralyzed during the Vietnam War, the US’s ‘improving relations with Moscow and … satisfactory ones with China’ offered the United Nations an opportunity to ‘correct the failings of the League of Nations’, to put an end to the ‘stalemate’ of the Security Council, and the possibility of the UN Security Council members to work together ‘in forging international unity to oppose Iraq.’[5] The United States did obtain this cooperation and thus had a ‘concert of power’[6] operating under the auspices of the United Nations.

When President Bush said repeatedly that the Gulf War would not be ‘another Vietnam’, what he meant was his administration’s determination overcome the opponents who argued that ‘Iraq was Arabic for Vietnam’[7], envisioning another unpopular, unwinnable war, this time in the desert. ‘Another Vietnam’ was the shorthand for ‘another defeat’. But ‘the Gulf is no Vietnam’ in all dimensions. Retired Colonel Joseph P. Martino of the US Air Force argued that there were no obvious similarities between Vietnam and the the situation in the Gulf in political cause, geographic conditions, historical context, and military circumstances. [8] In his analysis, Martino provided abundant statistical figures and information that strongly supported the contrast the made between Vietnam and the Gulf (Iraq).

The United States intervened in a ‘civil war’[9] in which its side lacked a popular base. The US sought to demonstrate that the war was the result of aggression by one state against another – North Vietnam versus South Vietnam – but could never do so convincingly. In the Gulf there was no doubt that the United States was seeking to reverse a blatant case of aggression. Consequently, whereas with Vietnam the international community was generally dubious of the way the war was both justified and prosecuted, in the Gulf the United States was part of a remarkable United Nations consensus. Vietnam’s awkward terrain of jungles and paddy-fields, its mysterious and determined enemy, and its confused political situation conspired to show up American power at its worst. The Gulf had created perfect conditions to show it off to full effect: open and relatively uninhabited terrain; an enemy prepared to fight a regular battle instead of shifty guerrilla warfare, yet inferior in the quality of both its manpower and is equipment; an aggressor who manifestly fitted the part. When US forces pulled out of Vietnam they were demoralized, almost mutinous, and enjoyed minimal respect at home. The mobilization of forces in Vietnam was based mostly on draftees while in the Gulf War this system was terminated and moved to a volunteer army… On all accounts, the Gulf was no Vietnam. As Freedman and Karsh concluded, ‘the Vietnam analogy was fundamentally misleading.’[10]

Furthermore, ‘Vietnam was a unique historical experience.’[11] Thus, any lesson drawn from Vietnam ‘may have only limited utility in determining the proper course of action in any subsequent scenario.’[12] Meanwhile, ‘there is little agreement on just what the lessons of Vietnam are.’[13] As discussed in Chapter One, President Bush and his predecessor, Ronald Reagan were convinced that the United States would have won in the Vietnam War had the US army not had ‘their hands tied behind backs.’ Both Reagan and Bush spoke of the lessons they drew from the Vietnam experience as if military power had not been used massively in Vietnam. By blaming only the ‘restraint’, if any, on the use of force for the American debacle in Vietnam, those revisionist leaders prevented themselves from ‘facing the truth’ since this hides the real shaping factors behind the Vietnam Syndrome. In his startling mea culpa memoirs, In Retrospect: the Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam, Former Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara identified ‘eleven major causes for our disaster in Vietnam.’[14] These major causes can be grouped into five categories- amounting to misjudgments of America’s adversaries, a failure to grasp the limitations of military power, misjudgments of the American people, misjudgments of international opinion, and general bad management. McNamara believes that pointing out the mistakes ‘allows us to map the lessons of Vietnam, and… to apply them to the post-Cold War world.’[15] McNamara lessons may seem flawed too, but at least it confirmed that there is little agreement on the lessons of Vietnam, even among policy-makers.

Of course, the Gulf War’s success could have rekindled the notion that massive uses of force can be the means to achieve moral, legal and practical interests that serve both the United States and the international community. However, because the nature of the conflict in the Vietnam War was so fundamentally different from that of the Gulf War, the application of this ‘lesson’ to the Gulf would prove to be ‘more the exception than the rule.’[16] When the Vietnam-like situations emerged, the Vietnam Syndrome came alive again.

[1] Parmet, Herbert S. (2001), George Bush: The Life of a Lone Star Yankee, Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick & London, p.477

[2] Hess, Gary R. (2002), op cit, p.153

[3] Borer, Douglas A. (1999), Superpowers Defeated: Vietnam and Afghanistan Compared, Frank Cass: London & Portland, Or, p. 212

[4] Donaldson, Gary A. (1996), op cit, p.141

[5] Bush’s memoirs, cited in Hess, Gary R. (2002), op cit, p.162

[6] Simons, Geoff (1998), op cit, p.332

[7] Borer, Douglas A. (1999), op cit, p.211

[8] See Col. Joseph P. Martino (Ret.), Vietnam and Desert Storm: Learning the Right Lessons from Vietnam for the Post-Cold War Era,

website: http://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/vietnamcenter/events/1996_Symposium/96papers/lesson.htm

[9] There has never been an agreed name for the Vietnam War. Different people from different political and academic perspectives use different names, such as the Vietnamese resistance against the American imperialism; war by proxies, civil war, American War…. On this point, see, for instance, Lawrence E. Grinter and Perter M. Dunn (eds.) (1987), The American War in Vietnam: Lessons, Legacies, and Implications for Future Conflicts, Green Wood Press: New York and London

[10] Freedman, Lawrence & Karsh, Efraim (1994), op cit, p.283

[11] Borer, Douglas A. (1999), op cit, p.213

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] McNamara, Robert S. (1995), op cit, p.320-3

[15] Ibid., p.324

[16] Jentleson, Bruce W. (2000), op cit, p.284